PHOTO

The Middle East and North Africa is home to about 578 million people, a population expected to grow to about 750 million by 2050. A quarter of them are currently food insecure, and 7 percent go to bed every night undernourished or hungry — mainly in conflict zones, rural areas and highly congested urban districts where the poor congregate.

Countries such as Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia waste about 250 kg of food per person every year. MENA countries waste about $60 billion worth, discarded by households and throughout the food supply chain from harvest to processing, retail, and food service.

This is not unique to the Arab world, or even the Gulf states, which are notorious for unsustainable food consumption, particularly during Ramadan. It is a global problem. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, a third of all the food the world produces, over 1 billion tons, ends up in landfill. The volume of food waste in industrialized nations is almost equal to sub-Saharan Africa’s entire food production capacity. Aside from the moral and humanitarian implications of discarding food still fit for consumption while millions go hungry, and the financial cost of farming, harvesting, transporting, packaging, and preparing food that ends up as waste, this has serious environmental implications.

First, throwing away food means expensive agricultural inputs such as high-quality seeds, special soils, feedstuffs, pesticides, and fertilizers are also wasted. This is especially concerning for a region where limited arable lands and water scarcity already substantially increase the costs of domestic agricultural production, vital to self-sufficiency, and of resilience strategies for insulating countries from global shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, discarded food ends up decomposing in landfills, resulting in the release of excessive amounts of methane, a far more harmful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. As the world races to drastically cut emissions by 2030, it is important to note that about 8 percent of greenhouse gas emissions from human activities could be reduced by sustainable food consumption practices.

Most MENA countries have made bold commitments to achieve the ambitious climate targets set in Paris. Gulf countries have committed billions of dollars in innovative environmentally conscious policies to cut greenhouse emissions without sacrificing economic growth. This will be crucial to building sustainable, greener, and far more resilient Arab societies and economies in the fast-approaching post-oil era.

Unfortunately, the region is still lagging in efforts to curb food waste, despite steps to address these challenges at the policymaking level and through attempts to raise public awareness. These efforts are slowly bearing fruit. More than 80 percent of people in the Arab world are aware of the financial, environmental, and social impacts of wasted food. Others even claim to have adjusted their consumption patterns, including extra actions to reduce waste, such as donating leftovers to charity organizations or using platforms like Wasteless Egypt, which directly connect households or individuals to those in need living near by.

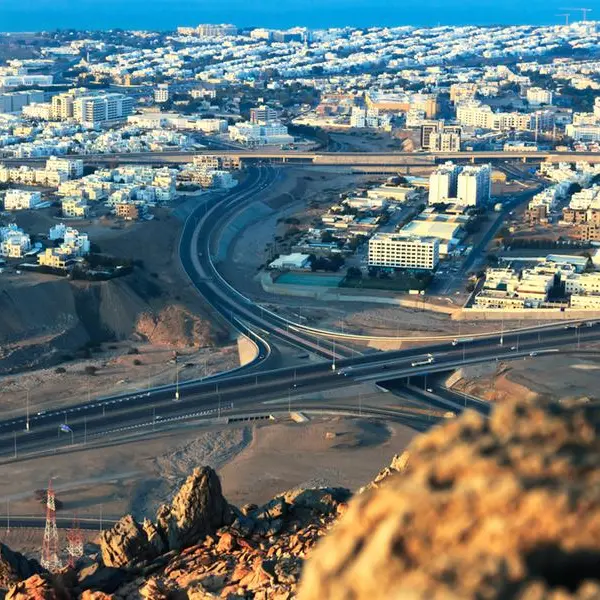

However, the biggest impact can be made only when governments tackle the primary drivers of unsustainable consumption, such as rapid urbanization, highly subsidized food contributing to rising consumerism, eradicating waste mismanagement and transforming cultural perceptions about food conservation. Indeed, the public may be aware of the challenges relating to food waste but there is still a palpable incongruity between the public’s positive view of sustainable practices and the continued consumption of finite resources.

An abundance of food in the Arab world’s “high consumption, high waste” societies will not improve the region’s food security. Rather, greater conservation and the reduction of waste will be vital in the building of resilient, self-sufficient, and environmentally conscious food supply chains, which will have a far larger impact on efforts to make the region more food secure.

It is impossible to reduce food waste to zero, but effective waste management strategies can be a source of opportunity. For example, the methane gas produced as discarded food decomposes is an untapped energy source. Composting and biogas technology are the two primary ways in which food waste can be recycled or repurposed, instead of the current preferred solution of landfill. Composting would be especially beneficial to the region’s agricultural sectors because it provides the organic materials necessary for sustainable soil fertility, which could also reduce the need for expensive fertilizers, and improve yields.

Biogas technologies, meanwhile, have matured in several European and Asian countries, allowing the conversion of food and other types of waste into beneficial products. Biogas facilities can become decentralized energy systems, which allow for the use of renewable sources to generate electricity, reducing fossil fuel dependency. When located closer to end users, they also reduce the environmental and financial costs of electricity transmission and distribution, while improving overall efficiency.

Beyond public awareness campaigns about sustainable food consumption, governments can build on the relative successes of these efforts to include responsible water and electricity use. Agriculture consumes more than 70 percent of the region’s limited water supplies, which energy-intensive desalination has tried to solve but has led only to increased fossil fuel use in electricity generation. Rapid urbanization has also shrunk natural habitats while the increased exploitation of maritime resources is contributing to coastal and undersea biodiversity losses.

The region can achieve its promised climate targets only if policymakers tackle this complex matrix of unsustainable consumption patterns in food, water, land, and even energy, with comprehensive engagement. The ultimate aim is to get as much of the public on board because legislation alone will fail to yield tangible results if the public remains culturally resistant to curbing excesses.

- Hafed Al-Ghwell is a senior fellow with the Foreign Policy Institute at the John Hopkins University School of AdvancedInternational Studies. Twitter: @HafedAlGhwell

Copyright: Arab News © 2021 All rights reserved. Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).