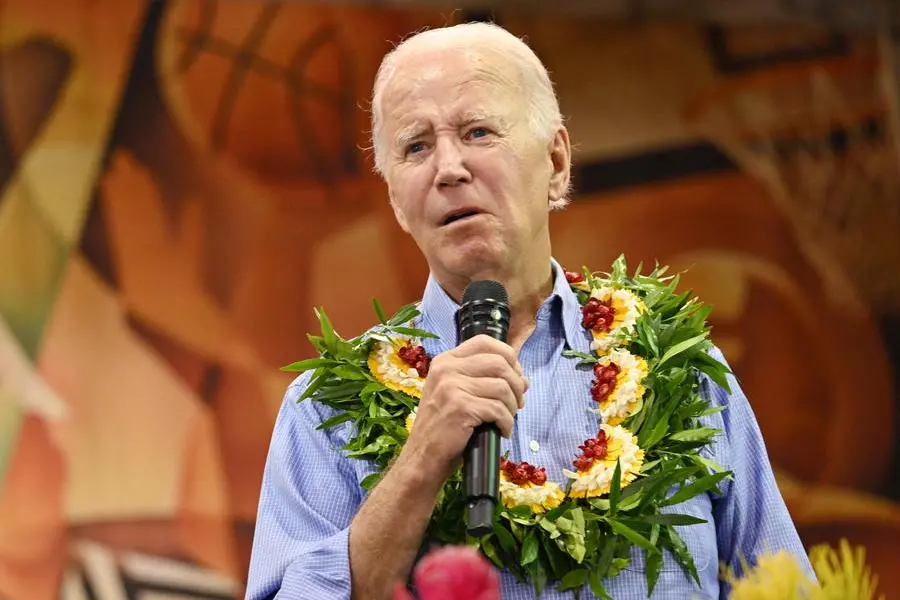

PHOTO

With a historic three-way summit with Japan and South Korea, President Joe Biden has further deepened the web of US partnerships in a determined signal to adversaries despite question marks on the political climate at home.

Since Biden took office in 2021, NATO has expanded and mostly closed ranks over Russia's invasion of Ukraine -- and, in clear if unstated responses to an assertive China, the United States forged a new three-way defense pact with Australia and Britain and ramped up work through the four-way Quad involving Australia, India and Japan.

The United States already has security alliances with Japan and South Korea, together the bases for some 84,500 troops, but will now also plan three-way, multi-year military exercises across all domains along with real-time information-sharing and a crisis hotline.

Jon Alterman, a senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said that alliances were "baked" into the mindset of Biden, who was a senator at the end of the Cold War.

Partnerships can increase other countries' faith in the direction of the United States, Alterman added.

"This administration believes deeply in the centrality -- not the importance, the centrality -- of partnerships," he said.

"The challenge is, all of our partners remember the previous administration, they look at the polling numbers, and they have absolutely no confidence in where the US is going to be in two years' time, five years' time or 10 years' time," he said.

Previous president Donald Trump loudly questioned the value of alliances, insisting that countries such as Germany and South Korea were not paying enough for the US troop presence and scoffing at NATO's commitments of mutual defense to all allies.

Trump is again seeking the White House and recent opinion polls have also shown softening support for US military assistance to Ukraine, which has totaled $43 billion since Russia's attack.

Asked about Trump at a news conference with South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida at the Camp David presidential retreat, Biden said that his predecessor's "America First policy, walking away from the rest of the world, has made us weaker, not stronger."

"America is strong with our allies and our alliances, and that's why we will endure," Biden said.

- Tougher task in Asia -

Whereas in Europe the United States has led a common defense for decades under NATO, in Asia -- seen by Biden as the critical region -- Washington has navigated individual alliances with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Australia and Thailand.

One reason for the hodgepodge has been historical animosity between Japan and South Korea, with the Camp David summit until recently unthinkable.

Yoon has turned the page by resolving a dispute over Japan's wartime forced labor of Koreans.

Yoon, Kishida and Biden said they shared the same vision of a "rules-based international order" -- a nod to China's muscle-flexing in Asia but also to Ukraine, of which Japan and South Korea have been prominent non-Western supporters.

China denounced the Camp David initiative, with state media saying the United States was raising tensions by creating a "mini-NATO," although there was no three-way mutual defense promise.

Shihoko Goto, acting director of the Asia program at the Wilson Center, doubted that the three countries were even aspiring to collective self-defense but said their new cooperation was part of an "interweaving" with existing alliance arrangements.

"As a single thread it may be weak, but because it is going to be part of that fabric and making it into a multi-layered approach, it would actually be really strong," she said.

- Risks await -

Biden has also moved bilaterally with countries concerned about Russia and China. He has said he plans to travel shortly to boost ties with Vietnam, whose tensions with Beijing run deep.

But one of his big bets, India, has stood firm on its historic refusal to join alliances and is also taking part this week in a summit with Russia and China of the BRICS bloc of emerging economies.

Trump is not the only wild card for the future. In South Korea, Yoon is only allowed a single term, which ends in 2027.

"If an ultra-leftist South Korean president and an ultra-right wing Japanese leader are elected in their next cycles, or even if Trump or someone like him wins in the US, then any one of them could derail all the meaningful, hard work the three countries are putting in right now," said Duyeon Kim, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security.