PHOTO

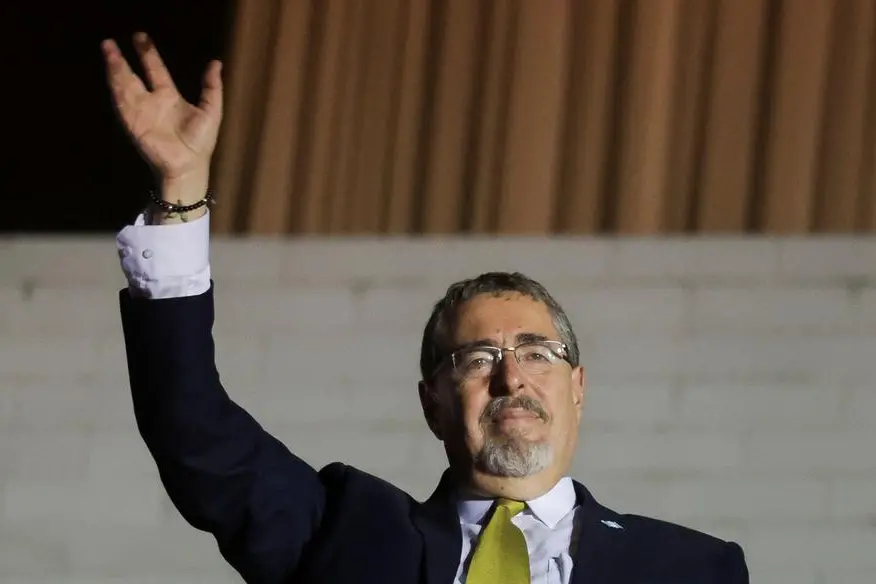

Guatemalan anti-corruption crusader Bernardo Arevalo was voted in as president on Sunday, preliminary results showed, a victory that until recently seemed impossible and which many voters hope will end years of rule dogged by allegations of graft and authoritarianism.

Arevalo, a 64-year-old ex-diplomat and son of a former president, had a 58% to 37% lead over former first lady Sandra Torres with 99% of votes counted.

His victory comes as violence and food insecurity roil the country, triggering fresh waves of migration. Guatemalans now represent the largest number of Central Americans seeking to enter the United States.

Arevalo has vowed to "purge institutions co-opted by the corrupt" and to get people committed to what he calls the fight for justice to return to Guatemala after scores of prosecutors, judges and journalists fled the country.

He faces blowback from entrenched interests and a Congress which his party does not control.

"This victory belongs to the people of Guatemala and now, united as the Guatemalan people, we will fight against corruption," Arevalo told a news conference after his victory.

President Alejandro Giammattei congratulated Arevalo on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, and invited him to start an "ordered transition" once results were formalized. The new president takes over Jan. 14.

Outside the Las Americas hotel in the capital, where Arevalo was due to speak, supporters gathered to revel in his victory, blaring horns, waving Guatemalan flags and cheering.

Many Guatemalans said they hoped Arevalo's win would herald a better future.

"We have waited for this moment for many years," said Carlos de Leon Samayoa, 27, as he celebrated on the streets of Guatemala City. "I feel pretty emotional."

Torres canceled her post-vote news conference scheduled for Sunday evening, local media reported.

Arevalo unexpectedly emerged out of political obscurity to build a large anti-graft movement with his Semilla party, after many other opposition candidates were barred from running.

His victory marks a repudiation of Guatemala's established political parties that wield huge influence.

When Arevalo landed a surprise second-place finish in June's first round of voting, official results were delayed as opponents alleged irregularities and his party was then briefly suspended at the request of a prominent prosecutor before Guatemala's top court reversed the ban.

Risa Grais-Targow, analyst at political risk consultancy firm Eurasia Group, said she expected attacks on Arevalo to continue.

"The ruling pact will likely continue to target electoral officials and Arevalo’s Semilla party with investigations ahead of January’s change in government," she said.

POLITICAL TENSIONS

Beyond his anti-graft policies, Arevalo said he wants to expand relations with China alongside Guatemala's longstanding allegiance with Taiwan. How he plans to do that remains to be seen, given China's policy that no country it has ties with can maintain separate diplomatic relations with Taipei.

This year, Honduras became the latest country in the region to

switch allegiance from Taiwan to China

.

There were no reports of violence or disorderliness at the polls.

A key representative of the Organization of American States (OAS), which has a team of 86 election observers in Guatemala, said the voting had gone smoothly. Eladio Loizaga, head of the mission, said the election had "fulfilled all the demanding obligations."

The election is being closely watched by the international community, including the United States, after campaigning was marred by attempts by some officials to remove Arevalo and his Semilla party from the race.

Outgoing conservative Giammattei has vowed to ensure an orderly vote and transition of power.

But many Guatemalans remain skeptical, having seen the government in recent years expel investigators from a U.N.-backed anti-corruption body and target judges and anti-corruption campaigners, many of whom fled into exile.

"The country Bernardo Arevalo will be receiving is very complicated," said Ana María Méndez, director for Central America at think tank Washington Office On Latin America.

"I see it more as a transition government, to restore the democratic values that have been broken in Guatemala."

(Reporting by Cassandra Garrison and Sofia Menchu in Guatemala City; Additional reporting by Herbert Villarraga and Diego Ore; Writing by Drazen Jorgic and Stephen Eisenhammer; Editing by Miral Fahmy, Stephen Coates and Gerry Doyle)