PHOTO

A slick new video that has gone viral on Russian social media platforms shows a taxi driver, a security guard and a fitness coach at work.

"Did you really dream of being this kind of defender?" the footage released by the Russian defence ministry says.

The video, set to dramatic music, then depicts armed men in full combat gear walking across a battlefield in thick fog.

"You're a real man! Be one!" says the ad, encouraging Russians to sign a contract with the defence ministry.

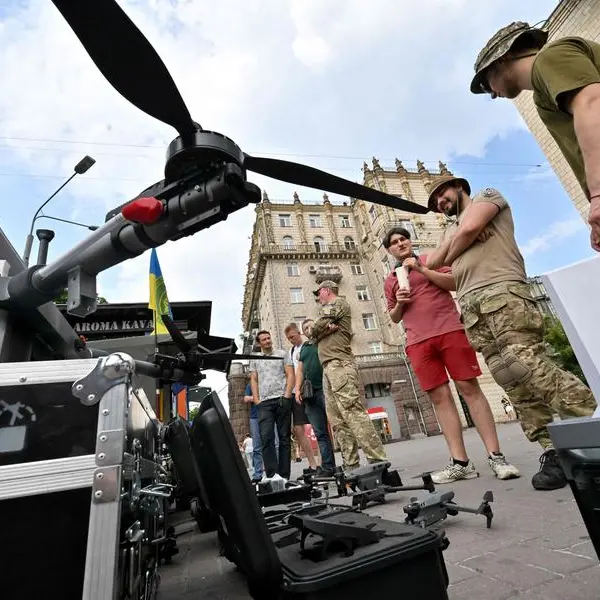

Moscow has launched an aggressive military recruitment campaign complete with videos and ubiquitous billboards as Kyiv gears up for a counter-offensive after months of stalemate in eastern Ukraine.

"Our job is defending the motherland," reads one of the billboards in the capital, showing three soldiers under a big blue sky.

"An honourable job and a decent salary," says another slogan.

Last September, President Vladimir Putin announced a "partial" military mobilisation -- Russia's first since World War II -- sending shockwaves across the country and prompting tens of thousands to flee.

Unwilling to announce a second mobilisation drive, Moscow has instead opted for a massive PR campaign, hoping to lure Russians with financial incentives.

- Tapping into macho culture -

The authorities have not disclosed their targets but various estimates say Moscow could be trying to recruit 400,000 volunteers.

"The authorities are almost certainly seeking to delay any new, overt mandatory mobilisation for as long as possible to minimise domestic dissent," British military intelligence said this week.

Those who sign a contract with the Russian defence ministry are promised a monthly salary of at least 204,000 rubles ($2, 450).

A notice on the Moscow mayor's website specifies that servicemen will be paid "at least 204,000 rubles" in "the zone of the special military operation", the Kremlin's official term for the offensive in Ukraine.

Those who take part in offensives are promised a daily bonus of 8,000 rubles (around $100) and at least 50,000 rubles (around $615) for capturing or destroying enemy weapons and military equipment.

Some praised the recruitment drive.

"In Russia, this is a good amount to support your family, and even your parents," Pyotr Lipka, a 21-year-old student from the southern city of Volgograd, told AFP.

"This makes sense: if a person defends his motherland, why shouldn't he get paid?" Lipka said, adding that signing a contract was better than being mobilised.

The PR campaign in support of the army builds on Russia's macho culture, promoting the image of a "real man" as strong and patriotic.

Last year, the authorities admitted embarrassing mistakes in their troop call-up for Ukraine, after some public outrage over students, older or sick people being mistakenly ordered to report for duty.

- 'Avoiding a new shock' -

Yevgeny Krapivin, 41, served as a professional soldier when Russia fought Chechen separatists in 1999-2002 and would like to sign up again to fight in Ukraine.

He said recruitment officers first turned him away, pointing to his age. "Then they told me: 'Wait. You can get a call at any moment'," he told AFP in central Moscow. "I am ready."

The launch of the new recruitment drive has coincided with preparations for May 9 celebrations marking the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany, which has reached a cult status under Putin.

This month Putin approved a controversial bill to create a digital draft system that could stop men from leaving the country.

Kremlin critics say the bill will greatly facilitate mobilising men to fight and clamp down on those avoiding the draft as the assault on Ukraine stretches into a second year.

Political observers say the Kremlin is keen to keep a tight lid on social discontent in Russia as economic troubles mount.

"Authorities clearly want to avoid a new shock, a new stress for society," Denis Volkov, head of independent pollster Levada Centre, told AFP, referring to a military mobilisation.

"And they've opted for a different scenario: to recruit volunteers," he said.

The campaign could be successful, especially in Russia's small, poverty-stricken towns, he added.

The new approach seemed to be working, Volkov said.

"We are not seeing any of the panic that there was in autumn," he said.

"No one is queueing up to go across the border."