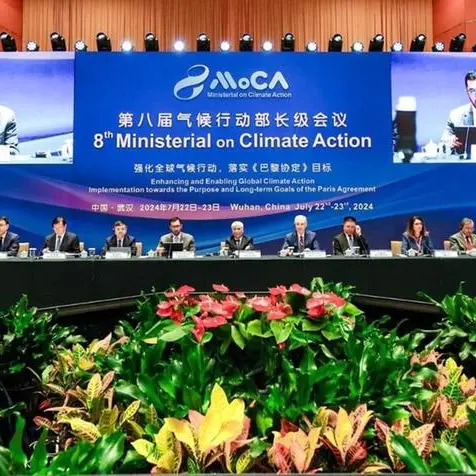

PHOTO

Negotiators at the COP28 climate conference in Dubai remained far apart on the future role of fossil fuels on Sunday as talks at the Dubai summit entered their final stage.

The question of whether the world should, for the first time ever, agree on an eventual end to the oil age has been central to the international conference where nearly 200 countries are trying to hash out a solution to climate change.

A coalition of more than 80 countries including the United States, the European Union and small island nations were pushing for a deal that includes language to “phase out” oil, gas and coal but were coming up against tough opposition led by the oil producer group OPEC and its allies.

OPEC issued a letter to its members and backers on Dec. 6 asking them to oppose any language targeting fossil fuels in a COP28 deal, and negotiators told Reuters that those delegations appeared to be heeding the call.

"I think there are still quite entrenched positions," said Adam Guibourgé-Czetwertyński, Poland's Deputy Minister for Climate, who is heading the country’s COP28 delegation.

"We are nearing the end, in terms of the time allocated for negotiations. But we are not quite there on the final outcome."

OPEC’s biggest producer and de facto leader Saudi Arabia, along with Russia and others, have argued that the focus of the COP28 should be on reducing emissions, not on targeting the fuel sources that cause them.

China’s top climate envoy, Xie Zhenhua, said on Saturday that a COP28 deal can only be considered a success if it includes an agreement on fossil fuels – though he did not say whether Beijing would back a “phase out” deal.

He said COP28 was the hardest climate summit of his career.

COUNTRIES AGREE SLEW OF COMMITMENTS

The latest version of the negotiating text, released on Friday, shows countries were still considering a range of options - from agreeing to a "phase out of fossil fuels in line with best available science", to phasing out "unabated fossil fuels", to including no mention at all.

Abating fossil fuels typically means reducing their climate impact by either capturing and storing their carbon dioxide emissions, or using other offsets. Carbon capture is expensive and has yet to be proven at scale.

Three sources told Reuters that the COP28 presidency did not intend to release another draft until Monday, something that would leave negotiators just one full day to resolve differences ahead of the conference’s scheduled end on Tuesday before noon.

"It's getting close to the end point, so that new text really has to find areas of convergence that's much beyond where we are right now," said Rachel Cleetus, a policy director at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The conference has yielded a slew of commitments from countries to hit targets like tripling renewable energy and nuclear power deployments, slash coal use, and curb emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas methane.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) said on Sunday that these pledges - if honored - would lower global-energy related greenhouse gas emissions by 4 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2030.

While the figure is substantial, it represents only about a third of the emissions gap that needs to be closed in the next six years to limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, as agreed to in the 2015 Paris Agreement, the IEA said.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, speaking at the Doha Forum, urged leaders at the COP28 climate conference to agree on deep cuts to emissions and stop global warming exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

Guterres said that despite pledges, emissions are at a record high and fossil fuels are the major cause.

"I urge leaders at COP28 in Dubai to agree on deep cuts to emissions, in line with the 1.5-degree limit," he said.

(Additional reporting by William James, Elizabeth Piper, Jake Spring, Sarah McFarlane, Valerie Volcovici, Simon Jessop, and Kate Abnett; Writing by Richard Valdmanis; Editing by Emelia Sithole-Matarise)