PHOTO

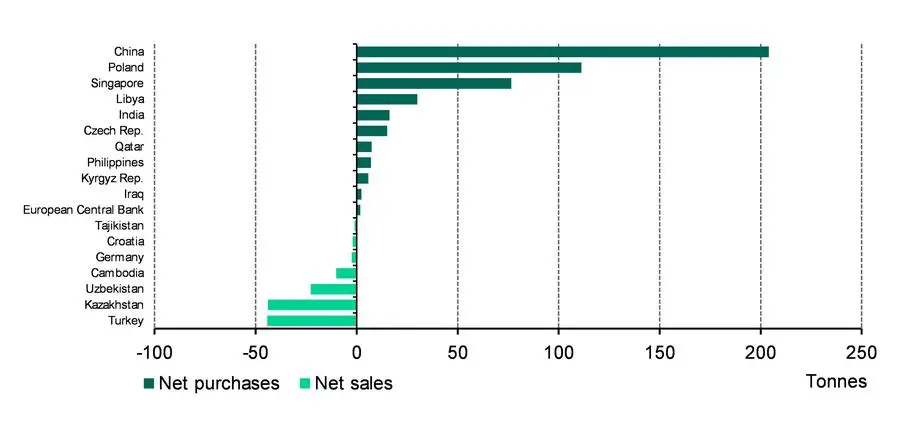

- The People’s Bank of China was again the largest buyer, followed by the Central Bank of Turkey and National Bank of Poland

- October saw higher sales volumes compared to the previous two months – led by Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

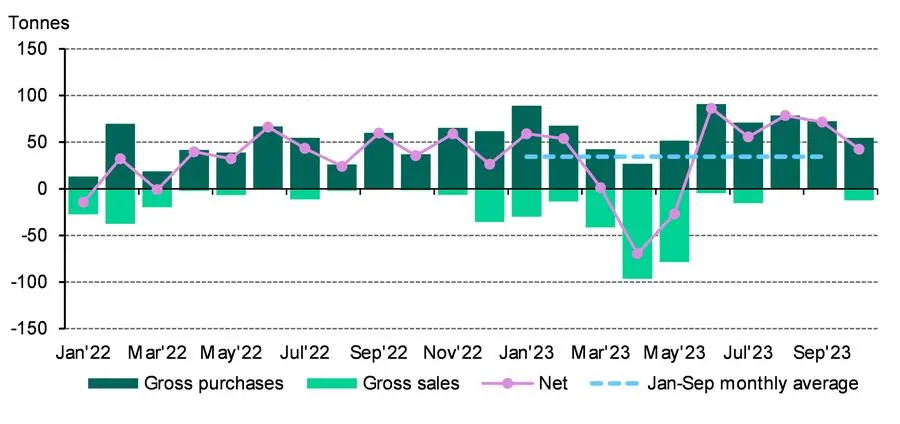

Central banks’ gold buying slowed in October but did nothing to alter the overall trend of robust buying that has captured the attention of gold investors. Reported global net purchases totalled 42 tonnes (t) during the month, 41% lower than September’s revised total of 72t, but still 23% above the January-September monthly average of 34t.

Central banks continued their buying spree in October*

*Data to 31 October 2023 where available.

Source: IMF IFS, respective central banks, World Gold Council

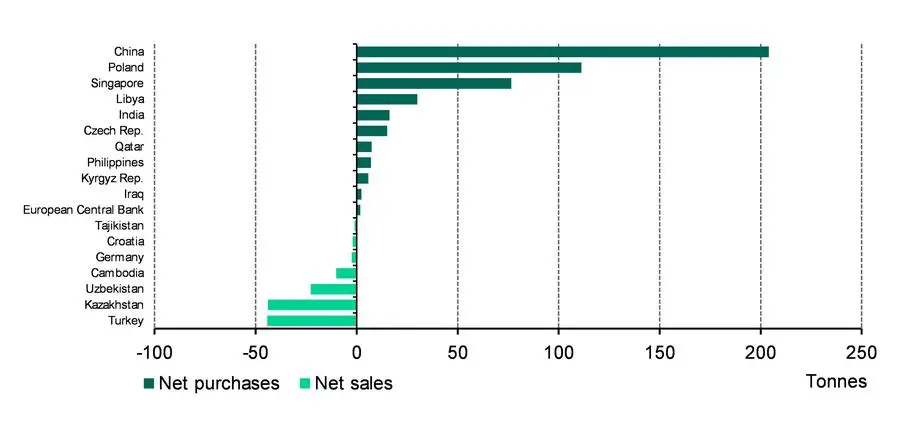

Country-level activity followed a familiar theme: a small number of banks accounting for the global total. The People’s Bank of China remained the largest purchaser, reporting the addition of 23t of gold to its reserves – the twelfth consecutive monthly addition. This brings its y-t-d net purchases to 204t and lifts its reported gold reserves to 2,215t. Despite the significant increase, reported gold reserves still account for just 4% of the bank’s total international reserves.

The Central Bank of Turkey also made a significant addition during the month. It bought 19t to increase its official gold reserves (central bank plus Treasury holdings) to 498t.[2] On a y-t-d basis the central bank still remains a net seller (44t) as a result of its heavy net sales between March-May.

Beyond these two banks, buying was more modest. The National Bank of Poland continued its recent buying spree, adding a further 6t to its gold reserves. Its gold holdings have now risen by over 100t this year, to 340t. The Reserve Bank of India (3t), the Czech National Bank (2t), the National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic (1t) and the Qatar Central Bank (1t) were the other significant buyers in October.

October also saw a higher volume of sales compared to August and September. These sales were driven by the Central Bank of Uzbekistan (11t) and the National Bank of Kazakhstan (2t). We have often noted that both banks frequently flip between net buying and selling, which is not uncommon for banks who buy gold from domestic sources.

Y-t-d central bank activity remains broad based, with purchases heavily outweighing sales*

*Data to 31 October 2023 where available.

Source: IMF IFS, respective central banks, World Gold Council

Even before October's net buying, we noted that 2023 was likely to be another colossal year of central bank buying.[3] Having started Q4 positively, this year’s central bank demand looks set to climb even higher.

For further information please contact:

Joann Joseph

Instinctif Partners

Joann.joseph@instinctif.com

Arief Zulkifli

Instinctif Partners

arief.zulkifli@instinctif.com

WorldGoldCouncil_ME@instinctif.com

About World Gold Council

We are a membership organisation that champions the role gold plays as a strategic asset, shaping the future of a responsible and accessible gold supply chain. Our team of experts builds understanding of the use case and possibilities of gold through trusted research, analysis, commentary, and insights. We drive industry progress, shaping policy and setting the standards for a perpetual and sustainable gold market.

[1] Based on monthly IMF IFS data and supplemented with data from respective central banks where available and not reported through the IMF at the time of publication. IMF IFS data is reported with a two-month lag, and while most institutions report on a regular basis, some may report with a – sometimes significant – delay. Figures may be subsequently revised as more data becomes available. The data used here informs but is distinct from the central bank demand estimates we report in Gold Demand Trends. Please see footnote 3 for more information.

[2] Turkey’s official sector gold reserves are the sum of central bank-owned gold and Treasury gold holdings. This is equivalent to gross gold reserves less all gold held at the central bank in relation to commercial sector gold policies (such as the Reserve Option Mechanism (ROM), collateral, deposits and swaps). For information on this methodology, click here.

[3] For purposes of Gold Demand Trends, central bank demand is defined as net purchases (i.e. gross purchases less gross sales) by central banks and other official sector institutions, including supra national entities such as the IMF and sovereign wealth funds where applicable. Our quarterly central bank demand data is sourced from Metals Focus, whose proprietary estimates of official sector activity incorporate various sources, including IMF IFS reports, international trade data, and others. As such, IMF IFS data is a subset of what is included in Gold Demand Trends. Both data sets are subject to revision as new information is made available and/or to accommodate late or updated data reported by official institutions.