PHOTO

NEW HAVEN – Economists are struggling to reconcile their upbeat views on the US economy with the angst of average Americans. The key measures of economic performance – growth, unemployment, and inflation – are almost perfect, putting the United States in an enviably strong position. But ahead of November’s presidential election, voters continue to cite the economy as a top issue. The main problem: inflation.

How can this be? To the exasperation of most economists, all this handwringing seems terribly misplaced. The COVID-19 shock to US prices from the spring of 2021 to late 2023 has subsided dramatically. Yes, we are still waiting for an all-clear sign that inflation is settling back down to the 2% target that the US Federal Reserve judges to be consistent with price stability. But there can be no mistaking a significant reduction in inflation risks.

Of course, there is an important catch: Even if inflation were to return to the promised land of price stability – although not as quickly as the optimists of the “transitory camp” initially expected – there is still a serious political problem with that result. Namely, prices are too high – and will likely remain elevated for many years to come.

By using the word “prices” instead of inflation, I am not splitting hairs. Inflation depicts changes in aggregate prices, which is very different from the level of the price index. That distinction bears critically on the political debate ahead of the election: President Joe Biden’s team is focused on the inflation rate while the American public is more concerned about the price level.

There is little debate over the progress on inflation. After surging to a post-pandemic high of 9.1% in June 2022, the overall inflation rate as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) has since receded to a 3.3% average over the past 11 months – an extraordinary reduction, or “disinflation,” over such a short period. However, inflation remains more than double the 1.5% average rate over the seven years prior to COVID and is significantly above the Fed’s 2% target, as seen through the lens of a slightly different metric, the GDP-based personal consumption expenditures price index.

But this near-complete recovery from the inflation shock of 2021-23 contrasts sharply with the still-elevated price level. Therein lies the political problem for Biden: As the chart shows, notwithstanding recent disinflation, the headline CPI in May was still fully 20% above its level in January 2021, when he took office.

Since January 2021, price levels remain especially elevated for energy (41%), transportation (40%), shelter (22%), and food (21%), which together account for 63% of the typical US consumer’s basket of goods and services. They are called essential purchases for good reason: families can’t live without them.

A back-of-the-envelope estimate suggests that, as of May, the aggregate price level, measured by headline CPI, is fully 15 percentage points higher than it would have been had the CPI maintained its 1.5% pre-COVID trajectory. No wonder Americans are so pessimistic about the economy. The big jump in prices, especially for basic necessities, overwhelmingly outweighs the drop in the inflation rate. And even if inflation were to fall further, as expected, the price level would remain uncomfortably high and continue to rise, albeit at a slower rate. A sustained period of outright deflation – a dangerous development for any economy – is the only way to push down the overall price level.

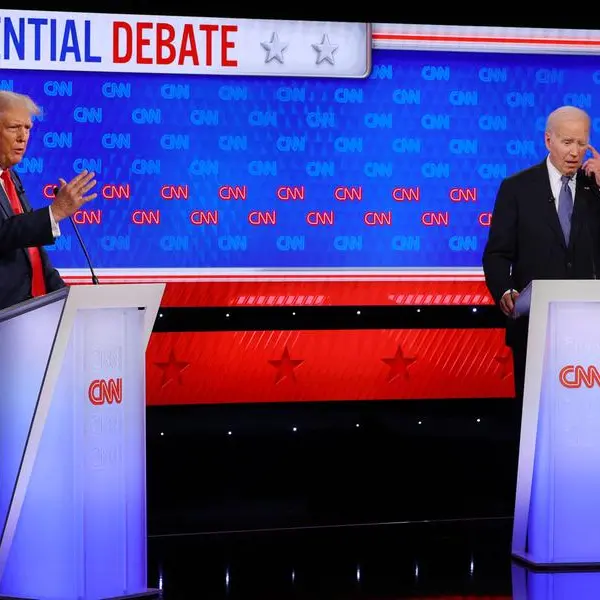

The juxtaposition between elevated price levels and sharply lower inflation is shaping up to be the defining economic problem of the upcoming US presidential election. In normal times, campaigns would feature a debate about which candidate has the best solution. Unfortunately, these are not normal times. The current state of US politics means that more attention will be paid to assigning fault. Ever since former President George H.W. Bush famously mocked the “vision thing” ahead of the 1988 presidential election, a myopic American public has placed much greater weight on the blame game.

Biden has offered a vision for solving this thorny problem, featuring, most notably, the Inflation Reduction Act and a strategy for de-bottlenecking supply chains. The presumptive Republican nominee, former President Donald Trump, would likely take a different approach, especially given his penchant for even higher tariffs, increased trade conflict, and a weaker dollar, all of which could stoke inflation.

But as the more likely blame game erupts, Trump will undoubtedly hold Biden responsible for the excessive rise in the aggregate price level since January 2021. Of course, Biden could turn around and blame the pandemic price shock – and, for that matter, America’s botched COVID response – on Trump.

Will the candidates take the high road of vision, or the low road of blame? Which one will make the more compelling case? I wish I could be more optimistic, but there seems to be little chance of a civil debate over common-sense economics. My advice is to hope for the high road but to be prepared for the low road, while simultaneously recognizing the important distinction between the level and the rate of change in prices.

Stephen S. Roach, a faculty member at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, is the author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China (Yale University Press, 2014) and Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives (Yale University Press, 2022).

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2024.

www.project-syndicate.org