PHOTO

Over the past decade, the Swiss private banking model has faced a series of significant challenges.

Swiss banks have not only been hit with post-financial crisis legislation aimed at preventing mis-selling of products but also global transparency laws forcing them to open up. Governments armed with whistleblower and data leaks have pursued individuals with money parked in Swiss accounts who were accused of attempts to evade tax.

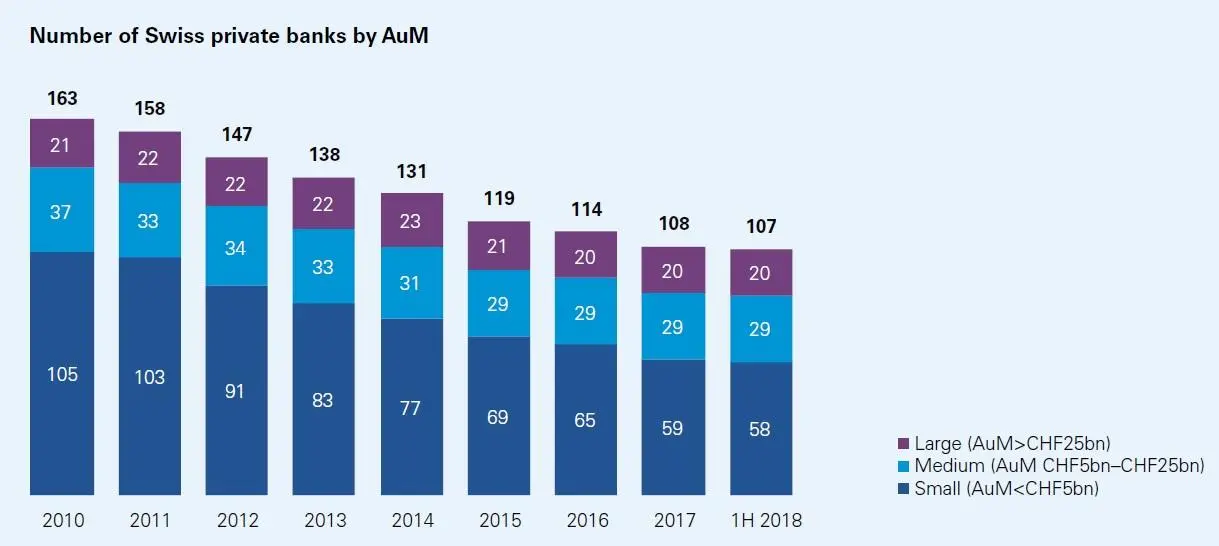

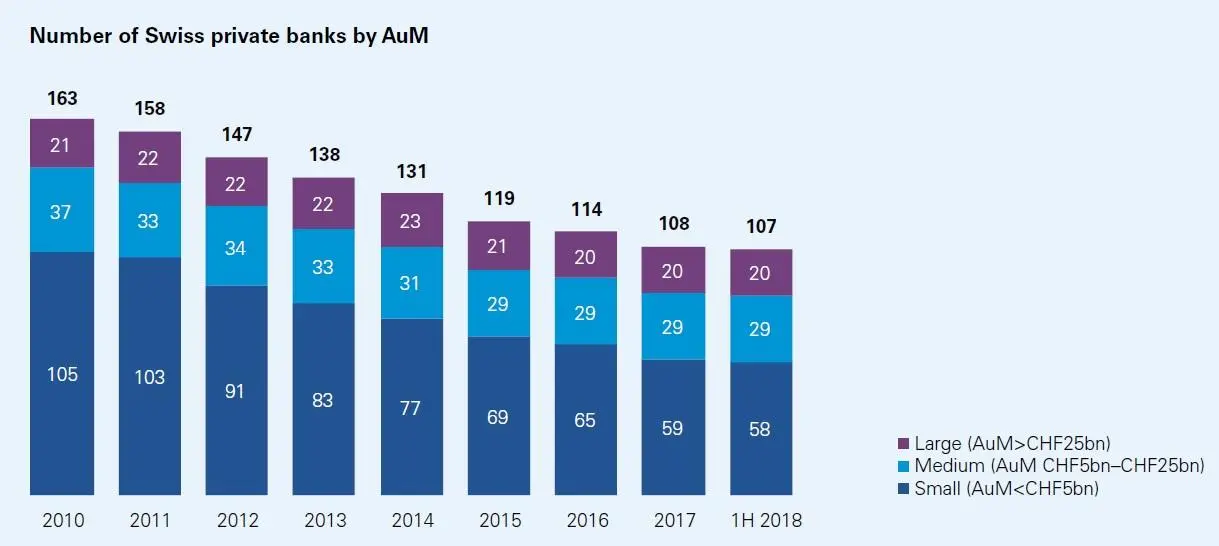

According to a study published in August last year by accountancy firm KPMG, between the start of 2010 and the first half of last year, more than one-third (34 percent) of Swiss private banks exited the market, with the total number declining in the same period by 56 to 107.

It said that seven Swiss private banks had gone out of business in an 18-month period from January 2017 to June 2018, with five being acquired by competitors and two entering voluntary liquidation.

Of course, for every bank vacating this space, there is an opportunity for those remaining to pick up market share - either through acquisitions or organic growth, and Union Bancaire Privée (UBP) has managed both, says the CEO of the Geneva-based bank's private banking arm, Michel Longhini.

“There has been a strong consolidation because, for example, we have been buying five or six different actors in the last eight years,” Longhini tells Zawya in an interview in the bank's Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) office at the end of last month.

Michel Longhini, CEO of private banking at Union Bancaire Privée

(Source: KPMG)

“Consolidation has happened for different reasons. I think the cost of doing business is the first one - the cost of implementing all of these regulations and things. So then critical size becomes a real issue. Plus, some strategic moves, some bigger groups who had some small private banking activity which they decided to divest,” Longhini says.

“Globally, the market is still a growing market,” Longhini says, adding that last year may have turned out to be “flattish” due to the decline in the value of equity markets which took place during the last quarter of the year.

Both sides of Brexit

UBP's six acquisitions include two deals announced last year for a pair of institutions that will sit either side of whichever deal is (or isn't) agreed as a result of Brexit. The bank announced the acquisition of Banque Carnegie Luxembourg in May, and London-based investment manager ACPI Investments in July.

The deal done in Luxembourg “was really to reinforce our European bank”, Longhini says. And although the London-based acquisition may be considered “a bit counter-cyclical”, he argues Britain will remain an important centre for the wealth management industry whatever happens as a result of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union.

“There are things that you may be able to do from London, some other things that you may not be able to do in the future covering European clients from London. But London for Middle East clients, for Asian clients, for many jurisdictions, is a key booking centre. It's difficult for a global player in wealth management not to be in London. Switzerland, London, Hong Kong, Dubai… places like this are places where the clients are having their money managed, so you need to be there," he says.

Acquisitions have helped the bank to grow its global footprint. Alongside deals in Switzerland to buy ABN Amro's Swiss business in 2011 and Santander's Swiss asset management arm in 2012, the bank has completed two deals that have given it much greater representation across Asia - most notably, in Dubai, Hong Kong and Singapore.

It acquired Lloyds Banking Group's international private banking business in 2013 and the international wealth management arm of private bank Coutts from Royal Bank of Scotland in 2016.

The ultimate result of its deal-making is that the bank has grown in size - assets under management at the end of 2018 stood at 126.8 billion Swiss Francs ($126.6 billion), compared to 80 billion Swiss Francs at the end of 2012.

The bank has also retained a strong tier-1 capital ratio (26.6 percent at end-2018), although net profit during the period has only edged up marginally - to 202.4 million francs at the end of last year, compared to 175 million Francs at the end of 2012.

In Dubai, both the Coutts and Lloyds deals expanded its team, and the bank currently has around 37 people covering a region that covers the Gulf and the Levant countries, but not North Africa, which is covered via UBP’s Geneva headquarters.

"It's a sweet spot compared to the other private banks in the region and it keeps us very agile, very active," Mohamed Abdellatif, head of UBP Middle East, says during the same interview. The bank has around $4 billion-$5 billion worth of assets under management in the region.

"We want to be in that sweet spot where you can do business but you don't want to have 20 RMs (relationship managers), everyone having a small book managing retail clients," Abdellatif explains.

"We hire RMs based on long track record of private banking experience. We don't hire junior (managers)," he adds.

Family matters

RMs typically work directly with families or family offices – “merchant families, families that have been in this region for quite some time,” Abdellatif says, adding that they value the fact that unlike many of its competitors, UBP remains a private bank.

"It's very easy when you share the same values," he says.

The bank, which turns 50 this year, remains in the hands of the children of its founder, Edgar de Picciotto, whose sons Daniel and Guy now serve as chairman and chief executive, respectively. Daughter Anne has also sat on UBP’s board since 2002.

"It's purely family-owned. Not listed. No intention to list, particularly. We have a very strong balance sheet," Longhini says.

Last month, UBP gained its first public rating by one of the major global rating agencies, with Moody's Investor's Services assigning an Aa2 rating to its deposits.

Asked whether the erosion of secrecy has made the Swiss banking model less appealing, Longhini says: "It would be a big mistake to reduce Switzerland to secrecy.”

He argues that the tradition of private banking in Switzerland is based primarily on trust, and on ”stability in the institutions and the people that you are dealing with, which is totally neglected or absent in many other countries”.

"Secrecy is a very limitative word," Longhini adds. "Confidentiality is also part of the DNA. It's regulated in Switzerland and it's part of the mindset... but it does not prohibit to a full tax transparency. Sometimes we mix the two terms."

He says that in many markets, “there is this kind of instability in the relationship which is part of different models - maybe more Anglo-Saxon or retail-based”.

“But what we can guarantee as Swiss institutions is the stability of the country, the stability of institutions (and) the long-term relationship.”

More millionaires

The Middle East is an attractive region, given the growing levels of wealth - consultancy Wealth-X's 2019 Global High Net-Worth Handbook published last month said the number of high net-worth individuals (defined as people with a net worth of $1 million or more) increased by 3.1 percent last year, to 571,550. However, the competition to manage their money is intensifying.

According to the Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA), the regulatory body for DIFC, there are 20 private banks in Dubai (although many local banks also compete in this space via private banking and wealth management arms). The regulator said in a statement via email that the wealth and asset management sector “has seen significant growth in the past year”.

It said that 2018 “was the strongest growth year to date in the DIFC's Domestic Fund Management Industry”, as the number of fund managers licensed by the authority grew by 46 percent, and the number of registered funds increased by 68 percent.

“As at 31 December 2018, we had a total of 69 Funds domiciled in the DIFC, of which 60 percent are QIFs (Qualified Investor Funds),” DFSA’s statement said.

There are also fintechs also looking to eat into this market. In November 2018, DFSA announced that robo-advisory firm Sarwa had become the first to graduate from its regulatory sandbox.

Although robo-advisory services have become more popular globally, with more than $202.6 billion of assets under management globally, according to a Q4 2018 Robo Report published on Wednesday by US-based Backend Benchmarking, Longhini does not see such services as providing competition for private banks.

“Honestly, not at all,” he says. “I did not see yet the type of clients we are talking to saying 'Look, I don't want to talk to your advisor any more - I want to talk to your computer'.

“Today, in particular in this business, there is not a single pure digital solution that has managed in any country to become a real digital competitor to private banking,” he said.

“It may happen - in a few decades, in my view - but not today," he said. "There is still, at a certain level of wealth, a need for a personalised service.”

(Reporting by Michael Fahy; Editing by Mily Chakrabarty)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Disclaimer: This article is provided for informational purposes only. The content does not provide tax, legal or investment advice or opinion regarding the suitability, value or profitability of any particular security, portfolio or investment strategy. Read our full disclaimer policy here.

© ZAWYA 2019